SOUTHERN CROSS (1999-2001)

November 2, 2012 § 5 Comments

As part of the project, SOUTHERN CROSS, the series, prospect critically surveyed the space of the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC). While historically, the Irish Republic was witness to other instruments of capital, this site was the first financial district in its history.

Established in 1987, the first phase of the IFSC opened on the north quays in Dublin’s inner city in 1989 with the second phase completed in 2000 – the European location for over half the world’s largest banks and insurance companies, and generating at its height, approximately 60% of the Republic’s wealth (IDA annual report 1999). This symbol of global aspiration and capital, the IFSC embodied ‘the Irish States monument to its position in a global economy’ (Carville 2002: 24) and was ‘driven by tax incentives, millions were spent to develop an international centre that would compare with The City in London or La Defense in Paris’ (MacDonald 2001: 14). The initial focus in its establishment was ‘jobs to market…[mostly] ‘back-office’ functions such as administration and processing; however, the goal [was] to establish higher value ‘front-office’ jobs…to ensure these companies stay here’ (Brennan 2004: 33).

Prior to the onslaught of the ongoing global economic crisis, the precariousness of the Republic’s position in attracting and retaining global capital investment would be reflected early in the cover headline in 2004 of an Irish business publication, ‘The IFSC – Finance Temple or Future Ghost Town?’ (ibid.: 1). The position has only been deepened further with the present circumstance. In 2006, the lack of regulation in the financial sector in the Republic was critically highlighted with terms like ‘tax haven’, ‘offshore’ and ‘shadowy entity’ being applied, alongside the plight of the majority of the workers in this sector, whom in addition to facing mass lay-offs, it was revealed how, ‘contrary to popular perception…[many] domestic financial services and IFSC employees were never in the big leagues when it came to making money’ (Reddan 2010: 15).

prospect surveyed the economic aspirations symbolised by the IFSC – a flagship of global capital and the architectural embodiment of the ‘new Ireland’ – and included images of the landscape and portraits of the young office workers, the new ‘physical labour’, inheriting the space from those who constructed it.

The accompanying series from SOUTHERN CROSS was titled, site and explored the transitory spaces between ‘what was’ and ‘what will be’ – the construction sites – being the birthing grounds of the ‘new Ireland’. The images, allegorical references to the effect of the changing geography on society incorporated landscape images made in the Dublin and county region, intersecting with portraits of the workers, those charged with the responsibility of transforming the landscape in the hope of fulfilling the desires of the society around them.

In its entirety, SOUTHERN CROSS (Gallery of Photography/Cornerhouse Publications 2002) was a critical response to the rapid development witnessed in the Republic of Ireland at the turn of the new millenium. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) brought about the largest economic transformation in the history of a country which never experienced the full impact of the Industrial Revolution. Completed between 1999-2001, the project critically mapped, through the spaces of development and finance, the economic aspirations and profound changes of a country on the western periphery of Europe. It presented the newly globalised labour and landscape, described then as the so-called Celtic Tiger Economy, being transformed in response to the predatory migration of global capital. In his essay, ‘Motionless Monotony: New Nowheres in Irish Photography’, addressing projects which charted the impact of the Celtic Tiger, including SOUTHERN CROSS, the writer and educator, Colin Graham observes in relation to the project:

‘evidence of the rasping, clawing deformation of the landscape, the visceral human individual in the midst of burgeoning idea of progress-as- building, propped up by finance-as-economics…it stands as an extraordinary warning of the future that was then yet to come (2012: 15).

Commissioned by the Gallery of Photography, Dublin in 2000 as recipient of the inaugural Artist’s Award, the exhibition of the same name took place in 2002. It was accompanied by a publication with the support of the construction sector of the trade union, SIPTU, and included the essay titled, ‘Arrested Development’ by writer and educator, Justin Carville and poem, ‘Implications of a sketch’ by poet and writer, Philip Casey. Further presentations included Cologne, Germany (2003), Lyon, France (2004), Paris, France (2005) and Damascus, Syria (2005).

References cited:

Brennan, C. (2004) ‘Financial Centre of Gravity’, Business & Finance (vol.40, no.14) 15 July-11 August, 32-36.

Carville, J. (2002) ‘Arrested Development’ in Curran, M., Southern Cross, Dublin: Gallery of Photography.

Graham, C. (2012) ‘Motionless Monotony: New Nowheres in Irish Photography’, In/Print, Volume 1, 1-21

IDA Ireland (2000) Annual Report 1999, IDA, Dublin.

MacDonald, F. (2001) 7 February, ‘Capital Architecture’, The Irish Times, pp. 14.

Reddan, F. (2010) 4 April, ‘Behind The Façade’, The Irish Times, pp.15.

‘Learning backwards’

August 31, 2012 § Leave a comment

A key concern of this project is the representation of labour. It is, therefore, critical to consider photographers and practitioners whom have sought to address such representations in meaningful, sustained and innovative ways. Known mainly for his images depicting the construction of the Empire State Building, here the specific reference is the early project work of Lewis Wickes Hine. Ground-breaking for its subject matter and the means and methods of representation that he engaged, this is further underlined in how the word, documentary, did not exist at this time in relation to the description of such visual undertakings.

In 1904, the teacher went to Ellis Island to witness the largest ever migration to the United States. Hine began making a series of immigrant portraits, which he would continue until 1930, later described as ‘incontrovertible documents of the human meaning of history’s greatest migration. The mass aspect of Ellis Island was left to the statisticians and social cartographers. Hine took care of the human equation’ (McClausland quoted in Rayner 1977: 42). Hine had met and befriended the wealthy businessman Arthur Kellogg, and through his patronage began documenting change for The Charities and Commons Magazine, later re-titled The Survey (Rayner 1977). He used photography ‘as a means to an end – to call attention to social injustice, to campaign for change and to celebrate the dignity of working people in the modern world’ (Panzer 2002: 3). He would devote his life to the portrayal of, among others, the plight of child labour, working conditions, the role of women, tenement living, veterans from the Civil War, disabled workers and the role of visible minorities. It is interesting to note how he circumvented issues concerning access to factories regarding child labour: ‘he pretended he was after pictures of machines…while one hand in his pocket made notes on ages and estimated sizes’ (Trachtenberg 1989: 201).

In this report (image above), one of 30 such documents in the U.S. Library of Congress collection, submitted with accompanying photographs to the National Child Labour Committee in 1909, Hine addresses the conditions of child labour in the Canning Industry in the American state of Maryland. Steeped in the observational and factual, anecdotal incidents are recounted as he encountered individuals working there, including the mother and widow, Mrs. Kawalski:

Many things has been misrepresented to her after they got there, she found that all the children, whose fare had been paid by the company, had to work all the time. The younger children worked some and went to school some, but they worked regularly as soon as they were able to stand up to the benches. “We lived xxx in rough shanties. It’s no place for children. They learn too much”. They had to furnish their own food and their fares were taken out of their earnings little by little. They didn’t get ahead any financially although it was a good year, at this place. “Call this slavery!” she said. (original delete marks, Hine 1909: 3)

Particular attention should be given to Hines’ subject position as manifest both in his working process and the framing technique employed. This relates primarily to a large part of what I would describe as his ‘early work’ from 1905 and up to, and including, 1920. Hine generally positioned his subject at eye level and in the centre of the frame. Whether individual or in groups, they presented themselves to the camera and the viewer. He maintained ‘careful notes’ of his encounters at all times and the work was usually accompanied by extended titles and captions (ibid.: 20). Hine was aware of the potential for allegory; ‘a picture is a symbol that brings one immediately into close touch with reality’ (Hine [1909] 1989: 207).

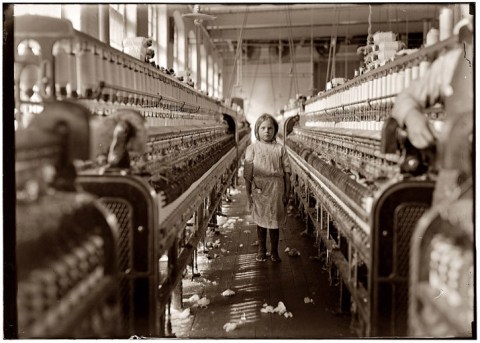

“December 3rd, 1908, A little Spinner in the Mollahon Mills, Newberry, S.C. Witness Sara R. Hine.” Lewis Hine

The Little Spinner is standing (image above). No more than 7 years of age, with hands by her side, there is a silence about her as she stares directly at the photographer, at the viewer. Hair barely combed, she is lost in size in the midst of the machinery surrounding her, all bolted to a floor spattered with traces of cotton. Her shoeless feet and little white smock dress are adorned with traces of the same cotton that is weaved web-like around her and her feet. She stares and we must return that stare for there is nowhere else to look, our perspective created by the row of machines denying us any escape. Her presence, our guilt? Our children, their futures? As we look at this young girl, certain histories and possibilities are posited, but nothing is complete and one now wonders the outcome of her fate. Hine demonstrates his understanding of the effectiveness of perspective in this instance. We as viewers are literally and visually forced to confront the human face of this unjust labouring situation. Aware of this potential, Hine coined the terms ‘social photography’ and ‘interpretive photography’ to ‘combine publicity and an appeal for public sympathy…to create a photograph often more effective than the reality would have been’ (Panzer 2002: 15). Here, simple in its presentation, the image exudes a subtle and silent quality amidst a scene which no doubt possessed harsh mechanical volumes. Hine himself noted:

She was tending her “sides” like a veteran, but after I took the photo, the overseer came up and said in an apologetic tone that was pathetic, “She just happened in”. Then a moment later he repeated the information. The mills appear to be full of youngsters that “just happened in”, or are “helping sister”. (Freedman & Hine 1998: 26)

Alongside his meticulous note-taking and written documentation, Hine maintained albums of his edited photographs (see above) – numbered and assigned, specific to each location where the images had been made. What is significant also is the sophisticated dissemination of the vast amount of photographs Hine generated.

Intended to affect public opinion and, thereby, government policy, there was a considered and critical mindfulness concerning the distributive possibilities of this visual material. For example, dedicated images surrounding narratives like this poster (image above) from Alabama addressing the plight of underage labour. While incorporating a sense of irony in the child now being the product, in turn it focuses attention on the fact that through/from the use of such child labour, factory owners could face the severest of penalties. The image below is what I would consider a key document from Hine’s work dating from 1907, ‘Night Scenes in The City of Brotherly Love’. Sponsored by Kodak, the pamphlet was published by the National Child Labour Committee.

‘Night Scenes in The City of Brotherly Love, 1907, Pamphlet, Lewis Hine (National Child Labour Committee)

There are ten sides to the document, nine of which contain portraits of young boys at work though the night of 4 November, 1906. Beginning with the first portraits of two boys at ‘EIGHT P.M’, the images continue along past ‘MIDNIGHT’ until ‘FOUR A.M.’, each portrait containing observational and anecdotal information collated by Hine. Made in Philadelphia at the beginning of the 20th Century, this significant document displays a sophisticated understanding of design, presenting us with an item which would easily fold up into something small and able to fit into a back pocket, a wallet or purse. In terms of dissemination and reaching an audience it is mobile, flexible and easily transported. Conceptually, ‘Night Scenes in the City of Brotherly Love’ is an evocative title for a document possessing nine portraits, most probably edited from a larger series of images, whereby these boys would, when refolded, return to face to face to one another, and rest upon one another. Hine highlights, with the assistance of the designer, the plight of these individuals, while simultaneously reminding the viewer that these young boys too belong to a community. As the artist and writer, Allan Sekula has commented of Hine’s work:

Lewis Hine is so exceptional, and so difficult to assimilate to models of early photographic modernism despite the modernity of his subject matter and the rigorous descriptive clarity of his style: he pursued strong aesthetic ends without losing sight of an ethical mission, or, to put it another way, he pursued an ethical mission without losing sight of strong aesthetic ends. (1997: 50)

In 1939, one year before his premature and impoverished death, the art historian, Elizabeth McClausland wrote about the significance of Hine’s role to photography:

To understand fully the magnitude of Hine’s achievement in documentary photography, one must understand not only the character of the man (his shyness and modesty which made it painfully difficult for him to force himself into factories, mills and slums where his photographic assignments took him) but also the fact that basically Hine did not know or care a great deal about technique. He learned photography backwards, as he frankly says. He took flashlights before he had ever taken a snapshot; he learned to make time exposures by going out and doing them. The modern scientific approach to the medium is completely alien to the Hine psyche. As said before, he blazed away; and by virtue of the sureness of his institution, and the single-minded directness of his objectives, he produced photographs of amazing beauty and powerful social content.(1974 [1939]: 18)

Sources quoted:

Freedman, R. & Hine, L. (1998) Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor, New York: Sandpiper.

Hine, L. (1909) ‘Child Labor In The Canning Industry of Maryland’, United States Library of Congress, <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pp/nclchtml/nclcreport.html>.

McCausland, E. (1971) ‘Lewis Hine: Portfolio (review)’, Image, Vol. 14/1, 16.

Panzer, M. (2002) Lewis Hine, London: Phaidon.

Sekula, A. (1997) ‘On “Fish Story”: The Coffin Learns to Dance’ in Camera Austria, Camera Austria, Graz, Issue 59/60, 49–59.

Trachtenberg, A. (1989) Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evans, New York: Hill & Wang.

A version of this text was included as part of my practice-led doctorate thesis, the abstract of which can be viewed here.

Summer Interns Having Lunch (1987)

July 18, 2012 § Leave a comment

Described as a pioneer of colour photography, Joel Sternfeld, lives and works in New York. This image by Sternfeld from 1987 focuses upon the youthful summer intern, a role defined as a crucial and critical rite of passage for those who desire a future on the street. Significant is also the timing of the photograph as it precedes the stock market crash of Black Monday that Autumn, viewed by many as a result of the increasing prevalence of neoliberal financial capitalism and the rising application of computer trading, particularly in the United States.

(Installation) Ausschnitte aus EDEN/Extracts from EDEN – PhotoIreland 2012

July 8, 2012 § 2 Comments

‘untitled’, section(map), Cottbus, Lausitz, Eastern Germany (glass slide, single projection)

Angelika, Tagebauarbeiterin, Tagebau Jaenschwalde, Lausitz, Eastern Germany, July 2008 (still, two-channel digital video, looped)

Having first visited the region in late 2003, seeking the impact of global capital in a periphery of Europe, as had been experienced in my native Ireland, I quickly realised that it was in fact the antithesis of this experience. Prior to the global economic collapse, but as evidenced by the above prophetic words of Marco, I encountered an emptying and the recognition that the same globalising forces which had transformed unrestrained the landscape of my origins, were indeed transforming this landscape through its forces of withdrawal and seepage – a globalised hemorrhaging. As a result, jobs were and continue to go further East while its younger population migrates to the West and in 2007, the Lausitz came last in a national survey addressing future prospects.

Informed by ethnographic understandings and incorporating audio digital video, photography, cross-generational testimony and artefactual material, the project has been constructed in the context of a landscape shaped by and inscribed with the utopic ideological aspirations of modernity – industrialisation, socialism and now at great cost, globalisation. In totality, the region invokes Marshall Berman’s ‘wounds of modernity’ resulting from the ‘cycles of destruction’ necessary for the functioning of capital. A pivotal emphasis for the project, is the catalyst for the region itself, the Tagebau and critically viewing it as perhaps a metaphor for late capitalism – finite, fragile and ultimately, unsustainable.

The production of the project has been generously supported by the Arts Council of Ireland.

Further information and location of exhibition available here.

Video documentation of the installation of the project as part of Encontros da Imagem in Braga, Portugal in 2011 can be viewed here.

Between Nature and Culture: Photography as Mediation and Method

June 24, 2012 § Leave a comment

From the series Beneath the Surface / Hidden Place 2007-10. Nicky Bird & Jan McTaggart: Foxbar, Paisley (Back of Annan Drive, 1977?/Back of Springvale Drive, 2007)

BETWEEN NATURE AND CULTURE: Photography as Mediation and Method

Symposium on Friday, June 29th, 2012

16 – 18 Ramillies Street,

London W1F 7LW

‘While we commonly expect photography to have a close relationship with the real, many practices positively engage with memory, landscape, identity and narrative. These themes rely heavily on photography as a means of translation and storytelling. This symposium invites theorists and photographers to speak about how they work with photography as a practice that serves to mediate the real’

Speakers include Ej Major, Nicky Bird and Mark Curran.

Organised by Dr Anne Burke and Dr Damian Sutton, Middlesex University.

1.30pm until 6pm

Further information can be found here

Contact: +44 (0)20 7087 9300/

Duty and Distraction

June 20, 2012 § Leave a comment

Die Angestellten: Aus den neuesten Deutschland/The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany by Siegfried Kracauer (front cover, Verso edition, 1998)

Published in 1930, Die Angestellten: Aus den neuesten Deutschland/ The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany by the writer and theorist, Siegfried Kracauer, was critically acclaimed. His friend and fellow author, Walter Benjamin, wrote, ‘ the entire book is an attempt to grapple with a piece of everyday reality, constructed here and experienced now. Reality is pressed so closely that it is compelled to declare its colors and name names’. Kracauer sought to address the new class of salaried employees of the Weimar Republic:

Spiritually homeless, divorced from all custom and tradition, these white-collar workers sought refuge in entertainment—or the “distraction industries,” as Kracauer put it—but, only three years later, were to flee into the arms of Adolf Hitler. Eschewing the instruments of traditional sociological scholarship, but without collapsing into mere journalistic reportage, Kracauer explores the contradictions of this caste. Drawing on conversations, newspapers, adverts and personal correspondence, he charts the bland horror of the everyday. In the process he succeeds in writing not just a prescient account of the declining days of the Weimar Republic, but also a path-breaking exercise in the sociology of culture which has sharp relevance for today.

Informed by sociology and discourse of the cinema, the publication was innovative both methodologically, for what could be described as its anticipated ‘ethnographicness’ and the resulting representational strategies of the ‘montage principle’. Kracauer employed a hybrid-like approach including ‘quotation, conversation, report, narrative, scene, image’ and as Inka Muelder-Bach, in her introduction to the English edition, observes:

His investigation…refrains from formulating its insight in a conceptual language removed form its material. Instead, Kracauer seeks to construct in that material. In other words, knowledge of the material’s significance becomes the principle of its textual representation, so that the representation itself articulates the theory.

The significance of its representational structure as means to articulate the everyday of ‘salaried employees’ material living conditions and that of the ideologies superimposed on this reality’ make it a important publication of continuing critical resonance.

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air

June 5, 2012 § Leave a comment

With a title originating from The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air is a visual art project by American-born, Amsterdam-based artist, Mark Boulos which seeks to address Marx’s notion of ‘commodity fetishism…where commodities seem to possess metaphysical qualities rather than material…(thereby) obscuring the labour relations which produce and distribute them’.

Boulos decided to focus on one of the most important commodities, oil and its ‘two end points, production and distribution’. He travelled to Nigeria and the Niger Delta, one of the most important oil producing regions on the continent of Africa and filmed Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND). The Niger Delta is noted for its extreme poverty in spite of the region’s oil wealth and the miltant group seeks to redistribute that available wealth. Subsequently, Boulos then filmed at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, one of the largest commodity exchanges in the world and which trades in commodities including oil futures.

First shown in 2008, it has been widely presented including the 2010 Berlin Biennale amongst others and is presently installed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In this interview, from 2008, with the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Boulos states how the majority of his work critically addresses ‘the relationship between ideas and material reality’.

The project takes the form of a two-screen installation, facing each other, the viewer is placed in between. Unable to fully view or engage with either film simultaneously, the viewer is required to make ongoing and repeated decisions in terms of a commitment regarding which way to look. Through its presentational strategy, the project appears to ceaselessly confront, not only those portrayed on the two screens, but those who perhaps find themselves in the middle.

‘THE SEA IS FORGOTTEN’

April 22, 2012 § Leave a comment

Based on the project Fish Story, by artist, writer and educator, Allan Sekula, his new film, The Forgotten Space, co-directed with Noël Burch, seeks ‘to understand and describe the contemporary maritime world in relation to the complex symbolic legacy of the sea’. Framed by the processes of globalisation, the sea represents, ‘slow time’:

Once you start thinking transnationally, you’re led to the sea: the ship is the first great instrument of globalisation…you can observe the compression of time and space in the modern world from the decks of a containerised cargo vessel.

In his notes, Sekula continues:

Our film is about globalization and the sea, the “forgotten space” of our modernity. First and foremost, globalization is the penetration of the multinational corporate economy into every nook and cranny of human life…our premise is that the sea remains the crucial space of globalization. Nowhere else is the disorientation, violence, and alienation of contemporary capitalism more manifest.

A significance of the original project and now the film, is the insight it provides concerning the complex yet determining relationship between labour and capital in all its globalised settings. The overarching context referenced in images from the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

The film has received a degree of media attention as witnessed in a recent interview with Sekula titled, ‘Filming the forgotten resistance at sea’, by the Guardian Newspaper addressing the project and its reception and can be found here. While a roundtable discussion between Sekula, Burch along with the cultural geographer and Professor at City University of New York (CUNY), David Harvey and art historian and curator, Benjamin Buchloh, following a screening at Cooper Union in May, 2011, can be viewed here.

Ultimately, while the film makes visible another labour narrative and its integral significance in a modernity that perhaps could be overlooked or indeed forgotten, critically, according to the curator and writer, Jennifer Burris, it equally proposes:

Forms of material resistance that not only reintroduce the maritime world as a space forgotten within the hypertrophied narratives of electronic trading and consumption-driven economies, it also argues for an understanding of the current financial crisis not as an aberration of global capital, but as a pathology intrinsic to capitalism itself.

Liquidated

April 8, 2012 § Leave a comment

Published in 2009, Liquidated: An ethnography of Wall Street, was the result of a three-year ethnographic study addressing the culture of high finance by Professor of Anthropology, Karen Ho of the University of Minnesota:

Based on this culture of liquidity and compensation practices tied to profligate deal-making, Wall Street investment bankers reshape corporate America in their own image. Their mission is the creation of shareholder value, but Ho demonstrates that their practices and assumptions often produce crises instead. By connecting the values and actions of investment bankers to the construction of markets and the restructuring of U.S. corporations, Liquidated reveals the particular culture of Wall Street often obscured by triumphalist readings of capitalist globalization.

Significant as a publication due to the innovative ethnographic grounding of its subject matter, in this short video, Ho outlines operating structures, the significance regarding ‘pedigree’, citizen complicity and the critical role of fear in this ‘culture of liquidity’: