Out Of The Pits: A Gursky Photograph and How to Represent Capital

December 20, 2012 § 2 Comments

A photograph of a frantic trading pit on an epic scale is installed on a gallery wall, its origins are the largest and oldest commodity exchange in the world. The photograph is titled Chicago Board of Trade II (1999) by German-born photographer, Andreas Gursky. Traversing the globe, Gursky makes images that reflect upon the human condition, as he sees it, manifest in urban, rural, cultural and industrial spaces. Although a former student of Bernd Becher (who worked professionally as an artist with his wife, Hilla Becher) at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy), Gursky has not completely subscribed to the dogma of strict objectivity, having always cropped and manipulated negatives when necessary and more recently, incorporated digital manipulation into his practice.

The Chicago Board of Trade is an exemplary site of modernity…in this location, everyday relationships to the potential of money and the necessity of trade become extreme. Financial professionals bring together flow, speed and technology in the pursuit of profits, and when thousands of them gather everyday, they help create something larger – the market.

Installed in a central passageway of London’s Tate Modern, the cultural anthropologist, Caitlin Zaloom, first encountered the image while in the city as part of her long-term ethnographic research on traders. The words quoted above form part of her response to the abstraction of capital that the image invokes, she continues:

a clear message about the velocity of money and its disordering effects in the global economy. The market takes in vast waves of capital and spews them out again in a logic all of its own. Yet the for the crowd of spectators around the photogaph, the commotion and dissarray are entrancing. It is unsettling to examine the picture closely, especially because a literal understanding of the physical space, or of the traders’ labor, is impossible. Instead it is easier to step back from the photograph and absorb the overall impression of the global financial beehive (2010: 2).

Her encounter with Gursky’s photograph forms the introduction to her book, Out of the Pits: Traders and Technology from Chicago to London (2010) and pivotally defines her methodological approach. While, understanding the functioning of such an aesthetic, Zaloom advocates as a priority to move beyond the abstraction of capital, as visually embodied in Gursky’s photograph – a function capital embraces also in the context of technological evolution regarding the labour of the traders themselves and their possible future abstraction – and a necessity, therefore, to look closer and in great detail at the apparatus of the global market:

Markets are objects of inquiry into the culture and economy of contemporary capitalism…today, the world’s powerful financial centers are the ones that need explanation. The mysteries of markets touch our lives, but few outside the financial profession understand them (2010: 11).

‘capital remains invisible’: L’Argent/Money (1928)

December 1, 2012 § Leave a comment

C’est proces est, peut-on dire…le proces de l’argent (You might say what is on trial…is money) proclaims the judge in the trial scene from the film L’Argent (Money). Directed by the French-born, Marcel L’Herbier and released in December, 1928, the film was an adaption of a story by the writer, Emile Zola. While Zola intended his story to be a ‘scathing representation of the French banking system of the Second Empire’, LHerbier sought in his ‘modernising’ version to ‘express, in all its modern virulence, his own contempt for money and capitalist speculation’. Centered on two duelling Bankers, the tale recounts their speculatory struggles against one another.

If somewhat ironically, the film cost almost 4 million French Francs at the time to produce, a fortune in today’s terms. L’Herbier had secured three full days access to the Paris Bourse (Paris Stock Exchange), where seeking to exploit the limited time, ‘there were fifteen hundred extras, about fifteen technicians, scaffolding that went up to almost the summit of the cupola, forty metres from the floor…and cameras everywhere’ (L’Herbier). Such scale is reflected throughout the film and, could be argued, evokes the privileged context it seeks to critically address.

Prior to the Stock Market Crash of 1929, the central narrative is framed by the structures of world financial spheres, through images of the application of communications technology, named world city exchanges repeatedly referenced to locating the viewer in the midst of the Open Outcry of the traders on the Parisian Trading Floor. One of the innovative dimensions to the film is the ‘absolutely unprecedented mobile camera strategy’ (Noel Burch), exemplified in one key sequence. The film’s focus of speculation is the cross-channel flight of a pioneer pilot and the possible riches to be exploited from the site of his destination and at the time of his departure, the propellors of his plane mimic the frenzied activity of the Trading Pit of the Paris Bourse, ‘recorded by an automatic camera descending on a cable from the dome toward the central stock exchange ring’ (Richard Abel). The activities are visually bound, synergies heightened, the speculative process and those involved, implicated.

The film critically acknowledges the interconnectedness of a then world economy, and while the scales of precarity and scope of speculation could be argued to have broadened, the resonance regarding the defining function of the market for the global neoliberal present are significant. The film studies and cultural historian, Richard Abel, writes:

L’Argent’s achievement in the end, rests on the correlation it makes between discourse, narrative and the subject of capital. Capital is both everywhere and nowhere, as Pierre Jouvet argues, echoing Marx; it motivates nearly every character in the film and is talked about incessantly, but it is never seen or – as the ‘dung on which life thrives’ – even scented. Capital remains invisible, and yet, its ideological manifestation, produces a surplus of effects…the film reflects on and critiques that which it cannot represent directly – the crucial reference point of a crisis in capitalist exploitation or, more specifically, the condition of western capitalist society on the brink of the Great Depression.

THE FUTURE STATE OF IRELAND

November 10, 2012 § Leave a comment

This forthcoming conference, part of a project of the same name, is taking place at Goldsmiths, University of London and will seek over the course of the two days:

to examine the repercussions of the crash for an island on the periphery of Europe from a cultural perspective. Examining cultural responses both pre and post economic meltdown, the conference will explore the possibilities of a new post-crisis Ireland: from the highly visible to the barely perceptible consequences of the crash and austerity, sources and limits of citizen resilience in crisis, the perceived value of cultural responses and active/passive citizenships. It will provide an opportunity for leading thinkers and practitioners across different disciplines to come together to discuss artists’ and citizens’ reactions and resilience in times of crisis and austerity.

A programme of visual and live art focused on crisis, resilience and endurance will intersect the conference schedule.

Speakers include Fintan O’Toole, Professor Roy Foster, Troubling Ireland Think Tank (of which Helen Carey is a project participant) and Kennedy Browne amongst others. The key organisers are Dr. Derval Tubridy, Stephanie Feeney and Nicola Bunbury. The conference takes place on 17-18 November, 2012 and full details regarding speakers and booking can be found here.

‘flexible accumulation’

November 5, 2012 § Leave a comment

‘At the economic level, capitalism adopts a new model of flexible accumulation which exploits and recreates difference. At the political level, the world of interacting states is transformed by relations that move above and below the nation’.

(Burawoy, M. et al. (eds)(2000) Global Ethnography: Forces, Connections and Imaginations in a Postmodern World, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 344)

SOUTHERN CROSS (1999-2001)

November 2, 2012 § 5 Comments

As part of the project, SOUTHERN CROSS, the series, prospect critically surveyed the space of the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC). While historically, the Irish Republic was witness to other instruments of capital, this site was the first financial district in its history.

Established in 1987, the first phase of the IFSC opened on the north quays in Dublin’s inner city in 1989 with the second phase completed in 2000 – the European location for over half the world’s largest banks and insurance companies, and generating at its height, approximately 60% of the Republic’s wealth (IDA annual report 1999). This symbol of global aspiration and capital, the IFSC embodied ‘the Irish States monument to its position in a global economy’ (Carville 2002: 24) and was ‘driven by tax incentives, millions were spent to develop an international centre that would compare with The City in London or La Defense in Paris’ (MacDonald 2001: 14). The initial focus in its establishment was ‘jobs to market…[mostly] ‘back-office’ functions such as administration and processing; however, the goal [was] to establish higher value ‘front-office’ jobs…to ensure these companies stay here’ (Brennan 2004: 33).

Prior to the onslaught of the ongoing global economic crisis, the precariousness of the Republic’s position in attracting and retaining global capital investment would be reflected early in the cover headline in 2004 of an Irish business publication, ‘The IFSC – Finance Temple or Future Ghost Town?’ (ibid.: 1). The position has only been deepened further with the present circumstance. In 2006, the lack of regulation in the financial sector in the Republic was critically highlighted with terms like ‘tax haven’, ‘offshore’ and ‘shadowy entity’ being applied, alongside the plight of the majority of the workers in this sector, whom in addition to facing mass lay-offs, it was revealed how, ‘contrary to popular perception…[many] domestic financial services and IFSC employees were never in the big leagues when it came to making money’ (Reddan 2010: 15).

prospect surveyed the economic aspirations symbolised by the IFSC – a flagship of global capital and the architectural embodiment of the ‘new Ireland’ – and included images of the landscape and portraits of the young office workers, the new ‘physical labour’, inheriting the space from those who constructed it.

The accompanying series from SOUTHERN CROSS was titled, site and explored the transitory spaces between ‘what was’ and ‘what will be’ – the construction sites – being the birthing grounds of the ‘new Ireland’. The images, allegorical references to the effect of the changing geography on society incorporated landscape images made in the Dublin and county region, intersecting with portraits of the workers, those charged with the responsibility of transforming the landscape in the hope of fulfilling the desires of the society around them.

In its entirety, SOUTHERN CROSS (Gallery of Photography/Cornerhouse Publications 2002) was a critical response to the rapid development witnessed in the Republic of Ireland at the turn of the new millenium. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) brought about the largest economic transformation in the history of a country which never experienced the full impact of the Industrial Revolution. Completed between 1999-2001, the project critically mapped, through the spaces of development and finance, the economic aspirations and profound changes of a country on the western periphery of Europe. It presented the newly globalised labour and landscape, described then as the so-called Celtic Tiger Economy, being transformed in response to the predatory migration of global capital. In his essay, ‘Motionless Monotony: New Nowheres in Irish Photography’, addressing projects which charted the impact of the Celtic Tiger, including SOUTHERN CROSS, the writer and educator, Colin Graham observes in relation to the project:

‘evidence of the rasping, clawing deformation of the landscape, the visceral human individual in the midst of burgeoning idea of progress-as- building, propped up by finance-as-economics…it stands as an extraordinary warning of the future that was then yet to come (2012: 15).

Commissioned by the Gallery of Photography, Dublin in 2000 as recipient of the inaugural Artist’s Award, the exhibition of the same name took place in 2002. It was accompanied by a publication with the support of the construction sector of the trade union, SIPTU, and included the essay titled, ‘Arrested Development’ by writer and educator, Justin Carville and poem, ‘Implications of a sketch’ by poet and writer, Philip Casey. Further presentations included Cologne, Germany (2003), Lyon, France (2004), Paris, France (2005) and Damascus, Syria (2005).

References cited:

Brennan, C. (2004) ‘Financial Centre of Gravity’, Business & Finance (vol.40, no.14) 15 July-11 August, 32-36.

Carville, J. (2002) ‘Arrested Development’ in Curran, M., Southern Cross, Dublin: Gallery of Photography.

Graham, C. (2012) ‘Motionless Monotony: New Nowheres in Irish Photography’, In/Print, Volume 1, 1-21

IDA Ireland (2000) Annual Report 1999, IDA, Dublin.

MacDonald, F. (2001) 7 February, ‘Capital Architecture’, The Irish Times, pp. 14.

Reddan, F. (2010) 4 April, ‘Behind The Façade’, The Irish Times, pp.15.

‘to know, realise and control’

October 8, 2012 § Leave a comment

‘The insertion of photography into the discursive field of management and the capitalist process of production, as a mechanism of objectification and as an instrument of subjection, is within the broader parameters of the desire of power of capital to know, realise, and control labour in its own image’

(Suren Lalvani (1996) Photography, Vision and the Production of Modern Bodies, Albany: State University of New York Press, p.139). Suren Lalvani was associate professor of humanities and communications at Pennsylvania State University until his early death in 1997, at the age of 43. Here is a short description addressing Lalvani’s work by Liz Wells from her edited publication, Photography: A Critical Introduction.

‘revolutionary’

September 23, 2012 § Leave a comment

The description given by a young female administrator of the Clearing Department at the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) in Addis Abeba, in response to a question of why she was working at the ECX, the youngest commodity market in the world. Established in 2008, the same year as the ‘offical’ global economic collapse began, the ECX is unique for its kind on the continent of Africa and as a ‘not for profit’ trading framework, one of a very small number of such markets, globally.

The exchange, trading primarily in coffee, sesame and peabeans, was founded by Dr. Eleni Gabre-Madhin. A member of the Ethiopian diaspora, Dr. Eleni studied in the United States, completing her doctorate in applied economics at Stanford University. The subject of a PBS documentary, The Market Maker, she wishes to use the traditional role of the market in Ethiopian society as the ‘fair’ means and method to end hunger.

State owned, prices and membership are, to a degree, regulated and the profits, accumulated by the ECX for its services as a trading platform, are re-invested into the organisation as a whole. To encourage transparency, emanating from a stated responsibility to the individual small farmer, farming collective or investor, the complete process from production, selection, storage to the point of sale and subsequent delivery is closely supervised in a framework of ‘open dialogue’. The exchange has grown from a permanent staff of 34 at the beginning to over 600 at present.

For the past month, following a extended process of negotiation, I have spent most of my time in the Ethiopian capital on one floor of one building, the Trading Floor of the ECX. While immersed in the working atmosphere of the traders and administrative staff, the functioning and ethos of this market framework appear to allude to the complexities embodied in the term, Market. Central to the functioning of capitalism, this term inspires descriptions, due to the global economic collapse, of fear or to be at the mercy of while here in Ethiopia, where 20 million of the country’s citizens (a quarter of the population) are dependent on the coffee industry alone, the framework presently installed at the ECX, appears to offer other possible descriptions.

‘Learning backwards’

August 31, 2012 § Leave a comment

A key concern of this project is the representation of labour. It is, therefore, critical to consider photographers and practitioners whom have sought to address such representations in meaningful, sustained and innovative ways. Known mainly for his images depicting the construction of the Empire State Building, here the specific reference is the early project work of Lewis Wickes Hine. Ground-breaking for its subject matter and the means and methods of representation that he engaged, this is further underlined in how the word, documentary, did not exist at this time in relation to the description of such visual undertakings.

In 1904, the teacher went to Ellis Island to witness the largest ever migration to the United States. Hine began making a series of immigrant portraits, which he would continue until 1930, later described as ‘incontrovertible documents of the human meaning of history’s greatest migration. The mass aspect of Ellis Island was left to the statisticians and social cartographers. Hine took care of the human equation’ (McClausland quoted in Rayner 1977: 42). Hine had met and befriended the wealthy businessman Arthur Kellogg, and through his patronage began documenting change for The Charities and Commons Magazine, later re-titled The Survey (Rayner 1977). He used photography ‘as a means to an end – to call attention to social injustice, to campaign for change and to celebrate the dignity of working people in the modern world’ (Panzer 2002: 3). He would devote his life to the portrayal of, among others, the plight of child labour, working conditions, the role of women, tenement living, veterans from the Civil War, disabled workers and the role of visible minorities. It is interesting to note how he circumvented issues concerning access to factories regarding child labour: ‘he pretended he was after pictures of machines…while one hand in his pocket made notes on ages and estimated sizes’ (Trachtenberg 1989: 201).

In this report (image above), one of 30 such documents in the U.S. Library of Congress collection, submitted with accompanying photographs to the National Child Labour Committee in 1909, Hine addresses the conditions of child labour in the Canning Industry in the American state of Maryland. Steeped in the observational and factual, anecdotal incidents are recounted as he encountered individuals working there, including the mother and widow, Mrs. Kawalski:

Many things has been misrepresented to her after they got there, she found that all the children, whose fare had been paid by the company, had to work all the time. The younger children worked some and went to school some, but they worked regularly as soon as they were able to stand up to the benches. “We lived xxx in rough shanties. It’s no place for children. They learn too much”. They had to furnish their own food and their fares were taken out of their earnings little by little. They didn’t get ahead any financially although it was a good year, at this place. “Call this slavery!” she said. (original delete marks, Hine 1909: 3)

Particular attention should be given to Hines’ subject position as manifest both in his working process and the framing technique employed. This relates primarily to a large part of what I would describe as his ‘early work’ from 1905 and up to, and including, 1920. Hine generally positioned his subject at eye level and in the centre of the frame. Whether individual or in groups, they presented themselves to the camera and the viewer. He maintained ‘careful notes’ of his encounters at all times and the work was usually accompanied by extended titles and captions (ibid.: 20). Hine was aware of the potential for allegory; ‘a picture is a symbol that brings one immediately into close touch with reality’ (Hine [1909] 1989: 207).

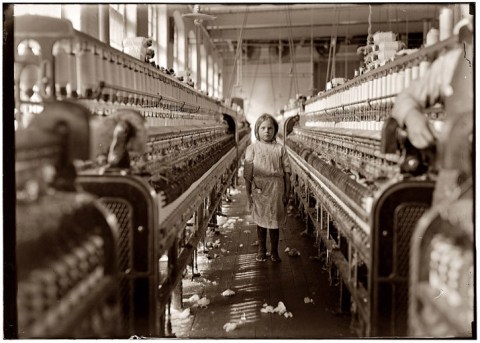

“December 3rd, 1908, A little Spinner in the Mollahon Mills, Newberry, S.C. Witness Sara R. Hine.” Lewis Hine

The Little Spinner is standing (image above). No more than 7 years of age, with hands by her side, there is a silence about her as she stares directly at the photographer, at the viewer. Hair barely combed, she is lost in size in the midst of the machinery surrounding her, all bolted to a floor spattered with traces of cotton. Her shoeless feet and little white smock dress are adorned with traces of the same cotton that is weaved web-like around her and her feet. She stares and we must return that stare for there is nowhere else to look, our perspective created by the row of machines denying us any escape. Her presence, our guilt? Our children, their futures? As we look at this young girl, certain histories and possibilities are posited, but nothing is complete and one now wonders the outcome of her fate. Hine demonstrates his understanding of the effectiveness of perspective in this instance. We as viewers are literally and visually forced to confront the human face of this unjust labouring situation. Aware of this potential, Hine coined the terms ‘social photography’ and ‘interpretive photography’ to ‘combine publicity and an appeal for public sympathy…to create a photograph often more effective than the reality would have been’ (Panzer 2002: 15). Here, simple in its presentation, the image exudes a subtle and silent quality amidst a scene which no doubt possessed harsh mechanical volumes. Hine himself noted:

She was tending her “sides” like a veteran, but after I took the photo, the overseer came up and said in an apologetic tone that was pathetic, “She just happened in”. Then a moment later he repeated the information. The mills appear to be full of youngsters that “just happened in”, or are “helping sister”. (Freedman & Hine 1998: 26)

Alongside his meticulous note-taking and written documentation, Hine maintained albums of his edited photographs (see above) – numbered and assigned, specific to each location where the images had been made. What is significant also is the sophisticated dissemination of the vast amount of photographs Hine generated.

Intended to affect public opinion and, thereby, government policy, there was a considered and critical mindfulness concerning the distributive possibilities of this visual material. For example, dedicated images surrounding narratives like this poster (image above) from Alabama addressing the plight of underage labour. While incorporating a sense of irony in the child now being the product, in turn it focuses attention on the fact that through/from the use of such child labour, factory owners could face the severest of penalties. The image below is what I would consider a key document from Hine’s work dating from 1907, ‘Night Scenes in The City of Brotherly Love’. Sponsored by Kodak, the pamphlet was published by the National Child Labour Committee.

‘Night Scenes in The City of Brotherly Love, 1907, Pamphlet, Lewis Hine (National Child Labour Committee)

There are ten sides to the document, nine of which contain portraits of young boys at work though the night of 4 November, 1906. Beginning with the first portraits of two boys at ‘EIGHT P.M’, the images continue along past ‘MIDNIGHT’ until ‘FOUR A.M.’, each portrait containing observational and anecdotal information collated by Hine. Made in Philadelphia at the beginning of the 20th Century, this significant document displays a sophisticated understanding of design, presenting us with an item which would easily fold up into something small and able to fit into a back pocket, a wallet or purse. In terms of dissemination and reaching an audience it is mobile, flexible and easily transported. Conceptually, ‘Night Scenes in the City of Brotherly Love’ is an evocative title for a document possessing nine portraits, most probably edited from a larger series of images, whereby these boys would, when refolded, return to face to face to one another, and rest upon one another. Hine highlights, with the assistance of the designer, the plight of these individuals, while simultaneously reminding the viewer that these young boys too belong to a community. As the artist and writer, Allan Sekula has commented of Hine’s work:

Lewis Hine is so exceptional, and so difficult to assimilate to models of early photographic modernism despite the modernity of his subject matter and the rigorous descriptive clarity of his style: he pursued strong aesthetic ends without losing sight of an ethical mission, or, to put it another way, he pursued an ethical mission without losing sight of strong aesthetic ends. (1997: 50)

In 1939, one year before his premature and impoverished death, the art historian, Elizabeth McClausland wrote about the significance of Hine’s role to photography:

To understand fully the magnitude of Hine’s achievement in documentary photography, one must understand not only the character of the man (his shyness and modesty which made it painfully difficult for him to force himself into factories, mills and slums where his photographic assignments took him) but also the fact that basically Hine did not know or care a great deal about technique. He learned photography backwards, as he frankly says. He took flashlights before he had ever taken a snapshot; he learned to make time exposures by going out and doing them. The modern scientific approach to the medium is completely alien to the Hine psyche. As said before, he blazed away; and by virtue of the sureness of his institution, and the single-minded directness of his objectives, he produced photographs of amazing beauty and powerful social content.(1974 [1939]: 18)

Sources quoted:

Freedman, R. & Hine, L. (1998) Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor, New York: Sandpiper.

Hine, L. (1909) ‘Child Labor In The Canning Industry of Maryland’, United States Library of Congress, <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pp/nclchtml/nclcreport.html>.

McCausland, E. (1971) ‘Lewis Hine: Portfolio (review)’, Image, Vol. 14/1, 16.

Panzer, M. (2002) Lewis Hine, London: Phaidon.

Sekula, A. (1997) ‘On “Fish Story”: The Coffin Learns to Dance’ in Camera Austria, Camera Austria, Graz, Issue 59/60, 49–59.

Trachtenberg, A. (1989) Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evans, New York: Hill & Wang.

A version of this text was included as part of my practice-led doctorate thesis, the abstract of which can be viewed here.