What is Marxism and Critical Theory? Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) Dublin, Saturday, May 25th

May 22, 2013 § Leave a comment

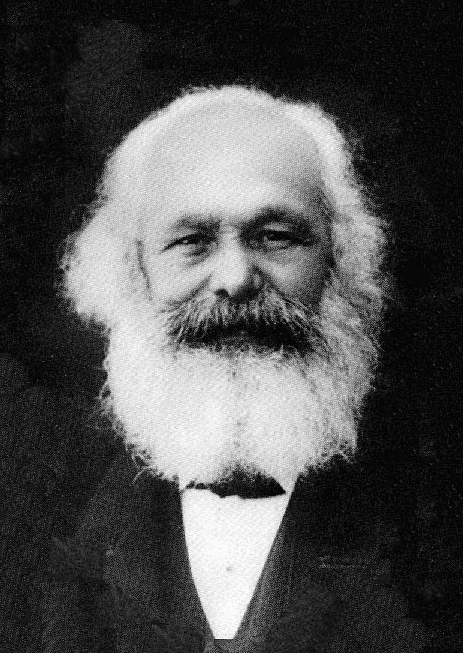

What is Marxism and Critical Theory?

Lecture Room, Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) Off-Site at NCH,

Saturday, May 25

Talk: 12:00noon – 1:00pm | What is Marxism and Critical Theory? An Introduction to Marxism and Critical Theory, presented by Declan Long and Francis Halsall, Lecturers, MA Art in the Contemporary World, NCAD.

Panel Discussion: 1.00pm – 2.00pm | Panelists include: Mark Curran (artist and educator), John Molyneux (socialist and activist blogger on Marxist theory and art), Declan Long and Francis Halsall, (Lecturers ACW, NCAD). This panel discussion considers the renewed interest in Marxist theory and its manifestations and relevance for contemporary art theory and practice. This discussion will draw on some of the central ideas addressed in the Intelligence Squared debate, Karl Marx was Right to be screened afterwards. To engage with the content of discussion we advise attendees to view this debate in advance. Please see details below.

Screening: 2.00pm – 3:45pm | Karl Marx was Right

A debate from Intelligence Squared titled Karl Marx was Right, broadcast on Tuesday 9 April 2013 can be viewed below

Booking is essential. Free tickets are available here.

No Longer Indifferent: The Photography of Milton Rogovin

May 1, 2013 § 6 Comments

He is dangerous to the internal security because of his strong adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles (internal FBI memo dated April 8, 1968)

In 1909, five years after Lewis Hine had made his first journey to Ellis Island to document mass migration, another American photographer, Milton Rogovin, was born in New York City. The son of Jewish migrants, he would, like Hine, have another career before making photographs, experiencing a significant upheaval in his life when everything would change. Having graduated from Columbia University and subsequently practicing as an optometrist, Rogovin moved to Buffalo, upstate New York in the 1930s. This was at the height of the Great Depression, and coupled with living in an area defined as socially deprived, Rogovin became politically active. As he comments; ‘this catastrophe had a profound effect on my thinking, on my relationship to other people. No longer could I be indifferent to the problems of people’ (1974: 12).

He became an outspoken critic of government social policies and became involved in the establishment of a union of optometrists and optical workers. He subsequently volunteered with the local branch of the communist party, a decision which would result in a call in 1957 to appear before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s travelling House Committee on Un-American Activites. In this era of Cold-War politics, such an appearance would cost him and his family their livelihood but would ultimately change the course of his life. Rogovin had an existing interest in photography, which he recalls in a radio interview:

When the McCarthy committee got after me, my practice kind of fell pretty low…my voice was essentially silenced, so I thought that by photographing people…I would be able to speak out about the problems of people, this time through photography*.

Influenced through his friendships with the photographers Minor White and Paul Strand, he would subsequently photograph in many countries around the world, from Mexico and Chile to Zimbabwe, always drawn to critically addressing social and political-based issues. Concerned with all forms of disenfranchisement, but primarily the role of labour, he quotes directly the words of the German artist Kathe Kollwitz to describe this motivation:

My real motive for choosing my subjects almost exclusively from the life of the workers was that only such subjects gave in a direct and unqualified way what I felt to be beautiful…Middle-class people held no appeal for me at all. Bourgeois life as a whole seemed to me pedantic…much later on, when I became acquainted with the difficulties and tragedies underlying proletarian life…I was gripped by the full force of the proletarian’s fate. (1974: 12)

Rogovin’s reasons may appear somewhat dated and naïve even politically incorrect in terms of contemporary discourse surrounding class, but the motivation to photograph those who he described as ‘the forgotten ones’ (ibid.: 12) underlines his profound sense of social and political responsibility to bring critical attention to both their situation and the circumstances.

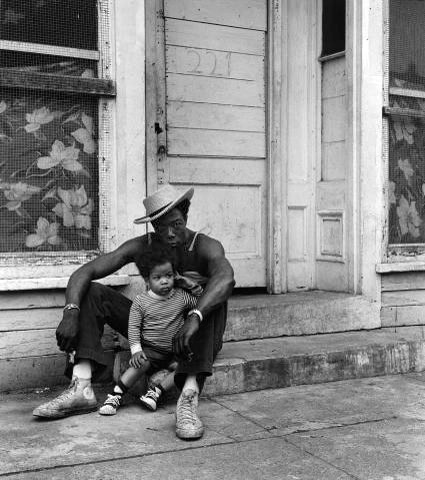

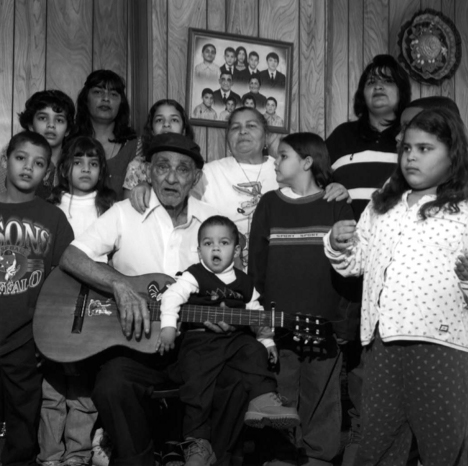

From the 1970s, Rogovin began to focus on his home borough of Buffalo and its inhabitants – a survey of miners and their families, steelworkers before and after plant closings, Native Americans on reservations in the state and a local Yemeni community, among others. The work lies within a humanist documentary tradition, evidenced in part by his application of black and white film, long associated with and evoking traditional photojournalism and reportage. However, what distinguishes Rogovin’s visual approach is his consistant and primary use of the portrait**. Acknowledging the work of Hine (Rogovin 1974) as an inspiration, many of the subjects within his images present themselves to the camera, facing forward looking and straight into the camera. As Rogovin describes:

I always asked permission before taking pictures. I wanted to get close and make people be the most important thing in the frame. I never directed them or told them how to stand, how to hold their hands, or what to wear. The only thing I asked them was to look at the camera. I liked it when I saw their eyes and that’s when I knew I was ready to make their picture. Typically, I would make 2 or 3 exposures. When you look at these pictures, you know there was no monkey business, and that I was not sneaking around trying to steal pictures of people. (Hirsch 2004: 8)

Describing the process of gaining the trust of the individuals he photographed, Rogovin draws attention to an understanding concerning the role of visibility and, as a result, the necessity for trust and the significance of complicity:

At first I was regarded with great suspicion, people thought the authorities sent me to spy on them.…[In] those days, people in such areas were not used to being photographed, or indeed being given any attention at all. I showed an interest, was polite, and tried to put people at ease…I would come back and give anyone I photographed a copy of their picture a few weeks later. Gradually I became known and trusted, and eventually people began to ask if I would take their picture. I remained in the area for the next three years. (Hirsch 2004: 7)

Rogovin added time to this process, in the form of long-term relationships, revisiting individuals and their families, which became an integral and critical aspect of his practice. He produced portraits, therefore, that I would describe as ‘over time’ – transcending time and must be therefore viewed simultaneously as both a singular experience but also beyond that singular experience one usually associates with the photographic encounter. In the images above, for example, the Rodriguez’s (images above and below), a couple and their family who lived not far from Rogovin, were first photographed in 1974, continuing to do so until 2002. Images such as these speak powerfully not only of the relationships and lives lived between the subjects portrayed but also of their intimate relationship with the photographer:

In Rogovin’s work the subject of each photograph, commands equal strength. Whether because of his respect and empathy for his sitters or the sincerity of his humanism and politics, this seemingly simple concept re-addresses the delicate balance of power between the observer and the observed.***

This innovative and critical use of the portrait was extended in 1993, when in collaboration with the anthropologist Michael Frisch, they published the book Portraits in Steel. The modern world that Hine had previously documented was becoming the so-termed ‘post-industrial’ landscape of the late twentieth century. Rogovin had begun in the 1970s to make a series of portraits of workers in the steel foundries in Buffalo. As the American steel industry collapsed amidst the increasingly globalised market of the 1980s and the once ‘Steel Belt’ was transformed into the now termed, ‘Rust Belt’, he returned along with Frisch to document this change. The result was a monograph, where portraits spanning almost 15 years appeared alongside the extended narrative of the testimonies gathered by Frisch. One continues to sense the relationship established with Rogovin in the apparent openness of the individuals taking part. Without such complicity, such a project could not have been undertaken.

Joseph stands (image above) shovel in hand, bare-chested with a vertical scar. The obvious use of flash highlights it as an environment usually lit only by the fires of the furnace. Here in in the steel mill at Bethlehem, Rogovin provides the transparent means with which the physical nature of this particular form of labour is revealed. Joseph is complicit in this undertaking in his stance and thereby completes the two-dimensional part of this meaning process. Now, the final completion of meaning will be undertaken by, and involve the complicity of, the viewer. Originally from the southern United States, Joseph grew up on a farm, and was two years short of service at the mill when he lost a leg to medical complications. This resulted in him never receiving a company disability pension and shortly after his operation the mill closed. He remains stoic in his advice for future working generations:

Well, the only thing I can tell them: get you some education, try to learn you a skill, because you will never see this industrial movement no more…that’s the reason I say the future is, they won’t be using their muscles, they’ll be using their brain (Rogovin and Frisch 1993: 312-313)

A significant undertaking, Portraits in Steel provides an extended visual and oral engagement with a changed industrial environment. The monograph is now a document to those who gave. In his discussion of the role of images and text, Rogovin’s collaborator on the project, Frisch writes:

[T]he book proceeds from a belief that all portraiture involves, at its heart, a presentation of self. It also does not deny that artifice, interpretation and even manipulation are necessarily involved in arranging the portrait session, rendering the images presented, and conveying them to others in some form or other.…[But] portraits do represent and express a collaboration of their own between subject and image maker, a collaboration in which the subject is anything but mute or powerless, a mere object of study…Stories given, rather than taken. (ibid.: 2-3)

In 2003, a short documentary titled Milton Rogovin The Forgotten Ones by the filmmaker, Harvey Wang, was released. A celebration of the work of Rogovin, the film provides insight into the long-term relationships formed by the photographer and those he sought to portray.

In January 2011, Milton Rogovin passed away in Buffalo, New York, one month after celebrating his 101st birthday.

Sources:

*As described by Milton Rogovin from an interview, ‘Milton Rogovin, Photographing “The Forgotten Ones”’ (2003), National Public Radio (NPR), broadcast 14 June 2003. Available here.

**Significantly, Rogovin’s application of the portrait, was described by his collaborator, the Anthropologist, Michael Frisch, as ‘pictures given, rather than taken’ (1993: 3).

***Quote from press release that accompanied the exhibition, ‘Milton Rogovin: Buffalo’ (Danziger Projects Gallery, New York, USA, October 20 – November 24 2007). Available here.

Texts:

Hirsch, R. (2004) ‘Milton Rogovin: an activist photographer’, Afterimage, September/October, 3–7.

Rogovin, M. (1974) ‘Six Blocks Square’, Image, Vol. 17/2, 10–22.

Rogovin, M. & Frisch, M. (1993) Portraits in Steel, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

A version of this text was included as part of my practice-led doctorate thesis, the abstract of which can be viewed here and here (scroll down).

Headlines (selection 2007-2010)

April 2, 2013 § Leave a comment

Lehman Brothers: Artwork & Ephemera

March 25, 2013 § Leave a comment

Lehman Brothers Auction at Christies, London, August 2010 (photograph by Linda Nylind/Guardian Newspapers)

Christie’s announce the auction of Lehman Brothers: Artwork and Ephemera which will take place at South Kensington on 29 September 2010 offering artworks and selected items of interest which once adorned the walls and offices of the British and European arms of the former banking powerhouse Lehman Brothers.

From the press release published in August 2010, under the direction of the administrators of the broke investment bank, once the fourth largest in the world, artefacts including the sign which had adorned the entrance to their offices in London’s Canary Wharf (image above) and also the contents of the art collection which included works by Gary Hume, Lucien Freud and the photograph, New York Mercantile Exchange 1991, by Andreas Gursky, were to be auctioned at market.

The timing of the auction was also significant, coinciding with the second anniversary of when the company went into administration. Citing the experience of the dismantlement of Enron, one of the administrators observes:

The brothers Lehman collected artwork which adorned their offices since the 19th century. Over the subsequent years, of course, as the business expanded and the leadership changed, so did their corporate taste in art. We are excited to be working with Christies to offer the art collection owned by the companies in Administration. The auction date was selected to approximately coincide with the second anniversary of the Administrations. We think that there are many people around the world who would like to acquire some art with a Lehman connection, and we have therefore timed the sale to ensure that potential buyers can view and bid efficiently online. As with the Enron auction, some seven years ago, when we had bids from 43 countries, we expect internet bidding to be fast and furious – having the capacity to cope with a large volume of global bidding was one of the key reasons why we chose Christie’s.

Recognised as one of the central pillars of the global market and subsequent architects of the global economic collapse, and mindful of the Gursky image, Lehman Brothers would appear to have been returned to the simultaneous site of its making and undoing.

MODERN TIMES Screening & Talk – Limerick City Gallery of Art (LCGA)

March 9, 2013 § Leave a comment

Unemployment is the vital question … Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work.

(Charlie Chaplin) 1931.

As part of the programme of the current exhibition, STRIKE!, at the Limerick City Gallery of Art, there will be a screening of MODERN TIMES (1936), written, scored and directed by Charlie Chaplin, at 2.00Pm on Monday, March 11th, 2013. This will be followed by a discussion from Mark Curran with specific reference to the visual representation of the conditions of labour and the resonance of Chaplin’s undertaking for the present.

Further information regarding the exhibition and full details of this event, can be found here.

The Breathing Factory at FORMAT 2013, Derby, UK

March 5, 2013 § Leave a comment

I mean we can keep throwing tax breaks at them but that’s just…that will only go so far…it’s a fool’s economy or a false economy or fool’s paradise or whatever you want to call it…I think we need to be…more cost effective and I don’t think…at the moment we really are…what we have got is, as I said, is…a well-trained, educated, kind of workforce…so that’s in our favour, but, again time will tell whether that’s enough…I don’t see it attracting everybody…I think they’ll always come in for the tax break and that’s probably the main reason they’re here for now…so I’m really not sure where this is going to be in 10-15 years time…you could have a lot of well-educated people walking done to the dole office (unemployment office) and you know…but like, I don’t really know where it’s going…you know…

(Cleanroom Supervisor, Canteen, Hewlett-Packard Ireland, 28 November 2003)

THE BREATHING FACTORY

A project by Mark Curran

Update: short video clip of the installation at FORMAT 13

Installation of The Breathing Factory, FORMAT13, Derby, UK from Mark Curran on Vimeo.

Steel Works by Julian Germain: ‘a postmodern visual history writing’

January 30, 2013 § 2 Comments

There was a time when to be from Consett was to be almost a celebrity. Catapulted into the media spotlight – photographed and interviewed by every kind of journalist, analysed by economists and sociologists, the subject of television documentaries and academic studies. Now the vast steelworks site, grassed over and landscaped, awaits council inspiration. Of the proposed schemes, which have included a Category A prison, the most bizarre has been a tourist park for the elderly entitled “The Coming Of Age”.

The above description originates from the book, Steel Works: Consett, From Steel to Tortilla Chips, published in 1989 to accompany the exhibition of the same title. Funded and presented by the Side Gallery in Newcastle, the project, by the English-born photographer Julian Germain, was a study of Consett in the North of England – ‘a town invented by four well-to-do gentlemen of Tyneside because of accessible mineral resources’27, becoming home to the largest opencast mine and steelworks in Britain. With its closure in the 1980s and the subsequent transformation of the site, the steelworks were completely dismantled involving the largest demolition project ever witnessed in Europe.

Germain employed diverse strategies of representation of the town and its community in order to re-present and re-assert, a sense and semblance of this once vibrant community. A page from Steel Works (above) is open to reveal a two-page, collage-like spread: a holiday photo-booth with a couple bedecked in sunglasses, the family and the family dog in the parent’s backgarden, groups of workers standing and sitting for the photographer, a smoke break, a tea break, and small samples of texts, ‘the factory lassies from Lancaster’ including ‘P. O’Leary’. The images appear haphazardly in display and somehow ‘speak’ to, of and about each other. A sense of a living community is portrayed. However, all are black and white and the clothes look ‘different’. It is not now.

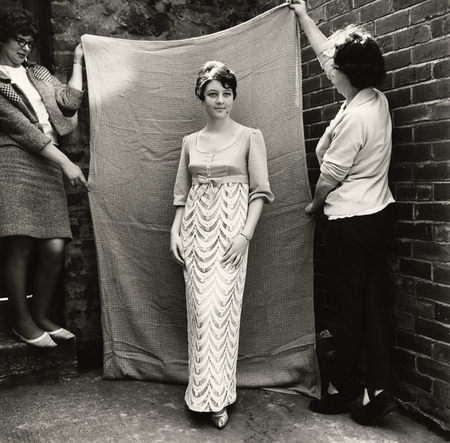

Germain presents individual testimony, anecdotes and interviews alongside his use of visual materials (above). We are invited to partake in familial memory by recourse to personal archives and family albums. Displayed alongside, are images by Don McCullin, made for the UK newspaper, The Sunday Times in the 1960s (below).

Germain also incorporates the work of another photojournalist, Tommy Harris, a local whom in addition to holding a full-time job at the steelworks, was responsible for photographing the surrounding community for local newpapers in the 1950s and 60s. Harris’s use of a square format camera would mean including details that would later be cropped. Yet, ‘it is these chance elements in Tommy’s uncropped photographs that make his work so revealing’ (quoted from exhibition text).

In the image above , a solitary hand in the upper left hand corner grasps the union workers banner echoing the central motif of solidarity.

The two women cling to the bedspread (above), stretched as a backdrop for a picture in the local paper, a daughter or a niece standing gracefully in the backyard. A sense of pride is evoked as both of the older women watch on, accompanied by a sense of purpose in their role, as this younger woman gazes out, towards somewhere. The project also included Germains’ own work in the region from the late 1980s. Through the ‘x’- marked glass of the image below, a labouring man with a carpenter belt shades his eyes and peers outwards and in doing so consciously or unconsciously implicates himself – this glass, t/his reflection, now part of a past or a possible future? As the final paragraph of the press release to accompany the opening of the exhibition, asked:

How do you define a community? The community of Consett has been defined and re-defined throughout its history…changing beyond recognition. The steelworks have been completely dismantled…what identity are people forming for themselves in the new Consett and how do they regard the past?

This work, collated by Germain, surveyed a period from 1910 until 1989 and has since been described as a ‘postmodern visual history practice’*. In a location where all physical traces of an industrial past had been removed, Germain constructed a social document of this local working community, through the reconstructive discourse emanating from the diverse representations presented, addressing an identity from the remnants and fragments of its visual and oral histories. More recently, George Baker’s description of the potential of photographs in the projects of the American artist Sharon Lockhart seems relevant and appropriate to the aforementioned projects and practices:

A genetic connection and return is contemplated, and the photographs emerge not so much as statements of appropriation and citation – proper to the debates carried on around photography at earlier moments of postmodernism – but as documents of historical remnants, continuities between past and present, the survival of what seems most precarious and impossible to contemplate in the current historical moment. (2008: 7)

Steel Works (installation view), Multivocal Histories, Noorderlicht Festival, Netherlands, 2009 (image courtesy Noorderlicht)

In 2009, twenty years following its publication, the curator and educator, Bas Vroege, included Steel Works in the exhibition, Multivocal Histories, at the Noorderlicht Festival in the city of Groningen in the Netherlands. Germain’s project was identified by Vroege as the central focal points for the conceptual framing of the exhibition in his selection of the projects included. Drawing on the history of montage, in the ethnographic sense, multivocality, is a critical representational strategy which acknowledges the many voices and multi-linearity of everyday experience in the construction of research. Vroege seeking more hybrid, transdisciplinary and ‘slow’ ways of working, writes in the accompanying catalogue:

Without the intention of doing so, Germain thus gave birth to a photographic practice that could be labelled ‘postmodern visual history writing’. Its essence resides in the fact that no one voice can be authoritative: history is by its nature the product of multiple voices and of recombining records from different moments in time. Or, as Frits Gierstberg recognized in Perspektief No. 41 in 1991: “By juxtaposing different types of photography Germain brings up for discussion their separate claims to authenticity and historical reality within the presentation itself”.

Sources:

*Germain’s practice was described as such in the brochure accompanying a conference titled ‘Work’. This was the inaugural event organised by the International Photography Research Network (IPRN), an initiative of the University of Sunderland, England (9-11 September 2005). Germain was present as a guest speaker

*Quote from text that accompanied the exhibition, ‘Steel Works: Julian Germain’ (Side Gallery, Newcastle, England, 1989)

*Quote from text that accompanied the exhibition, ‘Tommy Harris: Photographs of the County Durham steel town from 1949-1979’ (Side Gallery, Newcastle, England, 2003)

*Baker, G. (2008) ‘Photography and Abstraction’, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, article as part of year long project, WordsWithoutPictures, now available as a publication here

A version of this text was included as part of my practice-led doctorate thesis, the abstract of which can be viewed here

STRIKE!

January 25, 2013 § Leave a comment

As Ireland turns further into its Decade of Commemorations, Limerick City Gallery of Art presents STRIKE!, an exhibition exploring industrial disputes and workers resistance including the occurrence of Limerick’s extraordinary SOVIET, with material from Limerick City Museum, exploring the strike protest that existed in Limerick and ‘excited world attention’ in April 1919.

STRIKE! presents the Battle of Orgreave (an injury to one is an injury to all) by Jeremy Deller, directed by Mike Figgis, co-commissioned by Artangel and Channel 4. In a series of Films curated by Anthony Haughey, a wide range of response to industrial unrest, across many countries from Ireland to Argentina

The list of Films on show include:

-

STRIKE Sergei Eisenstein (94 minutes)

-

Dole not Coal COMPRESS Media (135 minutes)

-

Harlan County USA – Barbara Kopple (105 minutes)

-

Salt of the Earth Herbert J. Biberman (94 minutes)

- The Take Avi Lewis & Naomi Klein (87 minutes)

-

The Great Grunwick Strike Brent Trades Council (64 minutes)

-

Stand Together Brent Trades Council (52 minutes)

-

Look back at Grunwick Brent Trades Council (26 minutes)

- The Globalisation Tapes Vision Machine Project (70 minutes)

-

The GAMA Strike (60 minutes)

-

The Forgotten Space Allan Sekula (116 minutes)

The following films will be screened on dates to be confirmed, with guest speakers attending:

-

Modern Times Charles Chaplin (87 minutes)

-

161 Days Declan O Connell (45 minutes)

The Head Quarters Project calls on members of the community to contribute to a collective unearthing of buried memory of Limerick’s Soviet.

These explorations begin LCGA’s year-long presentation of the notions of Labour and Work in today’s world, with exhibitions throughout the year, drawing from the centenary of Dublin’s 1913 Lockout. It is, at the very least poignant, that this exhibition opens as workers from HMV concluded a sit-in for their rights and entitlements as workers, with many others realising the instability and problematic nature of working in Ireland and Europe today.

STRIKE! opened on January 24th and continues until March 15th. Further information available here

Sonntag presents THE MARKET (a progress report)

January 17, 2013 § 4 Comments

Sonntag would like to invite you to the installation of

THE MARKET (a progress report)*

by Mark Curran

Sunday

20 January

2 – 6pm

Exhibition dates

20 January – 23 January

Gossowstrasse 10, 4. floor

(Bell – Schiesser)

10777 Berlin

U1, U2, U3 Nollendorfplatz

U4 Viktoria – Luise Platz

Sonntag is a social sculpture that invites artists to collaborate and share their work in a domestic space. The project is realized on a monthly basis by way of a public invitation to a Sunday matinee where the invited artist‘s favorite cake and coffee/tea is shared with the audience.

This project was started in September 2012 by Adrian Schiesser and April Gertler.

*The event will feature work in progress from the project, THE MARKET.

Update images of the event can now be found here.

‘COMMEMORATION IS ABOUT THE FUTURE’

January 8, 2013 § Leave a comment

Having entered the centenary year of the Dublin Lockout, the words belong to the curator of this project, Helen Carey (Director, Limerick City Gallery of Art), and formed part of Helen’s presentation as part of a panel discussion held last October at the Arts Office of the Dublin City Council, The LAB. In the context of the exhibition, Digging the Monto, facilitated by Thomas Kador, the panel critically addressed the question of how to commemorate the 1913 Dublin Lockout, the 1916 Rising and the Treaty?

Thematically, Helen addressed the role of memory, the relationship between power and the construction of history and with such awareness, what is the role of contemporary visual art practice to mark this pivotal moment in Irish labour history with critical significance for the globalised present and the possibilities for a re-imagined future. Now available online, the presentations begin with Helen and are followed by Mary Muldowney (Oral Historian, Trinity College Dublin), Padraig Yeates (Lockout Historian & Writer),Roisin Higgins (Historian, Boston College), Pat Cooke (School of Art History & Cultural Policy, University College Dublin) and is chaired by Charles Duggan (Dublin City Council).

When we are talking about commemoration, we are talking about power and not necessarily history (Helen Carey)